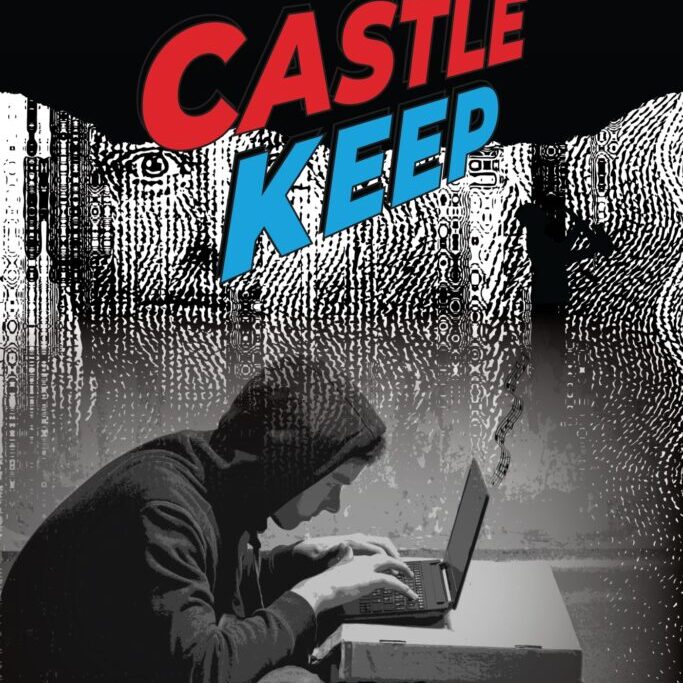

Here's a sneak preview (Chapter 1) of Castle Keep:

Black and Blue

Most nights, when I walk the cobblestone streets of Old Town and wander down the rows of ancient brick houses, which have stood side by side for so long that it's hard to tell where one ends and the next begins, I try to imagine what sounds George Washington might have heard when he surveyed the new port of Alexandria—at the time, just some docks, a warehouse, and a tavern.

I once read that Guglielmo Marconi, an early twentieth-century wireless inventor, believed that sounds never die; they travel through the atmosphere forever, fading as they go. With a sensitive enough instrument, we could still hear the laughter of loved ones we've lost, or echoes of the very first choral odes. I don't know if it's true, but I like that theory.

I once read that Guglielmo Marconi, an early twentieth-century wireless inventor, believed that sounds never die; they travel through the atmosphere forever, fading as they go. With a sensitive enough instrument, we could still hear the laughter of loved ones we've lost, or echoes of the very first choral odes. I don't know if it's true, but I like that theory.

So, I pause to try to catch drifts from the eighteenth century: the clip-clop and snort of horses, the clatter and squeal of wagon wheels, the rattle and groan of heavy chains as slave ships unload their migrant cargo.

I'm straining to hear the birth of new genres: maybe it's the first refrains of American rap, ripped from the rapid-fire chants of slave-trading auctioneers; or, the mournful hum of Southern blues rising up in response, infused with echoes of Africa, sorrow, and hope.

Musical roots fascinate me.

But all I get is the raucous din of the twenty-first century—the whine of a low-flying jet dropping its wheels as it banks into Reagan Airport, a delivery truck gunning it to make a yellow light on Prince Street, a city worker blowing leaves from the sidewalk. The eighteenth century seems fragile by comparison, no more than a wisp.

A gust rustles the barren branches overhead, whips away my wisp, and carries a sickly-sweet smell: fresh spray paint. It's cold, and as much as I enjoy passing through Old Town, I need to keep moving to stay warm.

Halfway down the block I pass by a dripping red-and-white slogan, minutes old, scrawled in giant letters across the brick wall of a low-slung parking garage: RAAGE RULES.

Graffiti tattoos the outskirts of Old Town, where I live, but here, near its center, it's rare.

People tell me that the historic city has always been a safe place to live. But lately, something's changed. Inspired by a national group known as Real Americans Against Government Exploitation (RAAGE), white supremacists have descended on Old Town in droves, holding hate-filled marches to resurrect the city's long forsaken slave-trading past. They've dredged up old conflicts, which has set people on edge. Maybe that's why I sometimes think I can hear the city's past.

Seeing the blood-red letters gives me the chills. I crank up my noise-canceling earbuds, tune in to Miles Davis, and turn the corner onto Strand Street. I like to take the long way home, through the heart of Old Town, past the harbor.

Until recently, I would get off work at 5:00 p.m., catch the Blue Line at Farragut West, and ride the Metro to King Street. For the past week, however, I've been working overtime, which has given me the opportunity to cross paths with Scarlett Dylan—the coolest (and hottest!) lady on the planet. She's a senior staffer for Jeremy Kant, who is President Burns's top adviser. Scarlett's in her late twenties and too old for me, but she doesn't know it because she thinks I'm someone else.

It's complicated.

I pause at Waterfront Park and pull out my earbuds. Despite the cold wind, I head to the end of the pier to listen to the black slap of the Potomac. It's a soothing rhythm. City lights flit across the choppy water. Upriver, the U.S. Capitol Building and Washington Monument blaze like torches. They're so close I could touch their jumpy reflections. Out here, without the noisy commotion of the twenty-first century, I can tune in to the past. The sharp gusts carry voices. For just a moment, I hear my mom and dad—the one a sweet violin, the other a soft bassoon.

I don't fight the tears. They get snatched up by the wind to join the dark river waters.

But I don't want to spoil the good vibe I still have from my end-of-day chat with Scarlett. So, I wipe my sleeve across my cheeks, jam my earbuds back in place, and let Miles Davis take over.

It doesn't take long for his serenading trumpet and Paul Chambers' meandering bass to reset my inner compass. I probably listen to "So What" from Kind of Blue at least once a day.

As I turn my back on the waterfront, and head toward the place I've been calling home for the past two months, Barrel Point Apartments, the river delivers an icy blast that makes my teeth chatter. So much for global warming. It's been as cold in Washington, DC this November as where I'm from, St. Paul, Minnesota. And that's saying something.

I snug up the zipper on my black fleece-lined sweatshirt, and pull the drawstrings tight to keep my hood from blowing back. The sweatshirt belongs to my brother, Joe. Since he served in the U.S. Army for eight years, it's official gear, with a yellow and white star sewn into the left chest, and yellow Army stripes on the sleeves. Ordinarily, I wouldn't wear anything military, but it helps me maintain the illusion at work. Plus, it's the warmest coat I own.

I turn down Franklin Street so I can duck into Moretti's Market to find something for dinner. At 7:00 p.m., I should know better. Moretti's is packed, and I don't feel like dodging shoppers down the aisles, so I settle for the dinner of champions: a premade turkey sub from the deli counter, a supersize bag of potato chips, and a two-liter bottle of Coke.

After paying, I cram it into my backpack, taking care to keep my laptop well-protected in its separate compartment, and head down South Washington Street, cranking my tunes to drown out the noisy traffic. These buds have "Layered Listening," which allows me to isolate sounds and turn up or down background noise using filters on my phone app. That's why I was willing to drop $300 on them. (Maybe I should have spent the money on a coat.) Even though they're amazing, the batteries suck. They last about two hours before they have to be recharged.

I'm about a block away from home when I suddenly realize I've made a mistake: Across the street from Barrel Point is a corner bar called Martha's (as in George Washington's wife). Its door faces the intersection of Green Street and South Washington. I know better than to pass by Martha's, but I guess I was so focused on getting out of the cold, and so caught up in John Coltrane coaxing those impossible scales from the keys of his tenor sax between Davis's riffs, that I lost track of where I was and forgot to go around the long way.

For a city kid, I come up short sometimes in street smarts. Martha's one of those places on the edges of Old Town that has been overrun by gangs of white supremacist skinheads. This particular gang has been terrorizing Barrel Point since before I moved here. I call this corner the Hate Zone. People know to avoid it, which is why, despite the busy time of night, there are no other pedestrians.

I'm just about to dart across the street—all four lanes of rush-hour traffic—when a gang member spots me. If I try to run now, they'll just chase me down like they have before. As discreetly as possible, I pull my earbuds from my ears and slip them into my front pocket. Whatever happens, I can't afford to lose them.

"Yo, lookie here, boys, if it ain't Skittles," says the short, dwarflike skinhead, who spotted me first. He aims the glowing tip of his cigarette at me and flicks it with such force that it flies upwind, ricochets off the side of my hood in a flood of sparks, and bounces into the road, where it's swept up by a passing car. It continues to spark and smoke even after it's been battered and smashed by traffic.

To white supremacists, "Skittles" became a code word after an anti-Muslim video went viral, showing how, in a bowl of Skittles, if even one is tainted, the whole bowl is bad. I made the mistake of wearing my dad's old kufi (a colorful Muslim prayer hat) one day while the skinheads were out in front of Martha's. Funny thing is, I'd never worn one before—I know about as much about the inside of a mosque as I do a temple or a church. My heritage may be Muslim, but my parents had lapsed before I was even born. I had the hat on for warmth, and for sentimental reasons.

The other three skinheads relinquish their posts, black boot heels propped against the brick wall beside Martha's front window, and step out onto the sidewalk to block my way. These are the lookouts. Inside and upstairs, there are more, partying probably, and selling drugs—meth, mostly.

I can tell they're drunk and high; they look agitated and wound up, like they've been playing video games for 12 hours straight. Between them, they have enough hardware drilled into their shaved skulls and enough ink shot into their skin that it's hard to tell them apart.

The short skinhead, however, can be singled out not only by his height, but also by a tattoo surrounding his left eye that looks like a pirate's eye patch. I'm guessing that's why his friends call him Patch. Despite his size—or maybe because of it—he seems to be their lead instigator.

"Where d'ya think yer goin', Skittles?" Patch asks in a slurred West Virginia twang.

He takes a step toward me and shoves me in the chest.

I stumble back but stay on my feet. "I don't want any trouble."

"Oh, t'ain't no trouble, no trouble t'all kickin' yer ass. Is it boys?"

Patch looks back at his friends as he's saying this. They all laugh and step closer. I'm taller than all of them, but lankier and inexperienced with street fighting.

Patch kicks me hard in the shin and shoves me again. This time I fall and land on my backpack. The bottle of Coke bursts open and sprays across the sidewalk behind me. The hard shell of my laptop digs into my side. I just hope it isn't damaged.

Before I have a chance to get to my feet, I'm surrounded. I curl myself into a ball to mute the impact of their stomping, kicking boots.

"We don't like yer kind," Patch grunts between kicks. "This ain't yer country. It's ours. And we're takin' it back from ay-rab scum like you. Yer days are numbered."

One of Patch's buddies spits on me. They call him Toothless because he's missing his two front teeth.

Thankfully, my specially reinforced backpack is protecting my spine, and since I'm curled up, the only part of me that's really taking blows is my arms, which I have wrapped around my head. Still, every couple of kicks partially connects with my skull, and I see stars. The fleece-lined hood doesn't do much to soften the impact.

As pain and humiliation set in, street sounds fade—somewhere in a distant recess of my mind, I hear Coltrane's sax calling to me. It's a familiar riff from "Blue Train," with the scales timed perfectly to the flurry of blows I'm enduring.

I first heard Louis Armstrong in my sixth-grade science class. That's right, science. We were studying astronomy. My teacher played selections from a replica of the Golden Records launched with Voyagers 1 and 2 in 1977. I don't know why, but when I imagined those gold-plated disks, mounted to the front of Earth's tiny mechanical envoys, ferrying our greatest hits across the cosmos, something in me stirred. When Louis Armstrong's Melancholy Blues began to play, the muted beat of my inner musician throbbed to life and has been keeping time ever since. It's not lost on me that there aren't many teens obsessed with jazz, but to me it feels as natural as breathing air.

Now, to escape the Hate Zone, I'm hurtling into the dark and soundless void beyond the reach of our sun, perched atop Voyager 1's titanium frame, swinging my legs and snapping my fingers. We're headed for distant galaxies, bearing the best of Earth: Mozart, Bach, Beethoven, Chuck Berry, and, my favorite, Louis Armstrong. Even though Coltrane never made the best-of-Earth final cut, "Blue Train" blares from my satellite's dish, awakening the sleepy star-stuff, which turn to see who dares disrupt their silent eternity.

Ba-da-di-da-daaa, doo-doo, ba-da-di-da-daaa…

One of the blows catches my face and jolts me back to terra firma. Blood gushes out, filling my mouth with a warm, salty tang that I spit onto the sidewalk. My tongue reflexively assesses the damage. My front tooth is loose and may be chipped.

Suddenly, the kicking stops.

"Whatchyoudoin', amigos?" I hear a familiar voice calling from down the street.

It's Manuel. He's the leader of a vigilante gang that defends this corner of Alexandria whenever the police are busy elsewhere, which seems to be most of the time.

Manuel's well-known and well-liked around Barrel Point. He's saved my ass from these skinheads before. He once told me that "we immigrants need to stand up for each other, Moe, or these white haters will take over everything."

"This ain't your business, taco," Toothless growls.

"Hey, how come you callin' me names?" Manuel turns to his friends. "That's not nice, is it, compos?"I hear murmurs as they encircle the skinheads.

I use the distraction to stagger to my feet.

"Is that my boy, Moe?"

Manuel steps between Toothless and Patch and wraps his arm around me, steering me away from them. The skinheads know better than to interfere. Even though Manuel can be nice, his gang has a street-fighting reputation. Plus, they outnumber the skinheads two to one.

"For a smart kid, you sure learn slow," Manuel teases. "You got to stay away from this corner."

"I know," I mumble. "I'm sorry, Manuel."

He pats me on the back. "De nada."

Unable to contain his rage, Patch steps in front of me and Manuel. He's a head shorter than both of us, but that doesn't stop him from trying to bump chests with me.

"You got lucky this time, Skittles," he snarls.

"You ought to pick on someone your own size," Manuel jokes.

His friends laugh, which only enrages Patch all the more. He reaches toward his vest. It looks like he's ready to pull a gun.

"Get going, Moe," Manuel says to me, shoving me out of the way.

When I don't leave right away, he hisses, "¡Sal de aquí!"

I don't need to know Spanish to see that Manuel wants me out of here—now.

With my ears ringing, my mouth bleeding, and my head aching, I charge across Green Street to Barrel Point. When I reach the far curb, I stop and turn to see what's happening. Flashes of metal glint in the streetlight as Manuel's gang closes in on the skinheads. A few other pedestrians pause on the corner to watch, too.

Patch pulls his gun from his jacket and aims it at Manuel. I gulp. The woman next to me lifts her phone, snaps a picture, and dials 9-1-1.

Besides being in the Army, my brother Joe was a hunter, so I'm familiar with guns, but not like this. Not one man pulling a gun on another out in the streets from anger and fear. It's the Hate Zone at its worst.

Manuel doesn't flinch. He says something that makes his friends laugh. It's just a distraction because, quick as a snake, he snatches the gun from Patch and pounds him on the head with the butt. Patch drops to the sidewalk.

I turn and hurry to the far side of the apartment complex.

Juke, my roommate, has a one-bedroom corner apartment on the third floor of a walk-up. In the winter, when there are no leaves on the trees, there's a view (sliver) of the Potomac through one of his living room windows. His bedroom, which overlooks a courtyard, is small, and crammed with all his stuff. In fact, the whole apartment looks like something out of "Hoarders."

Juke collects a lot of junk—mostly instruments and electronics like bass guitars (three), amps (four), mixers (two), and computer gear (uncountable)—so it feels crowded, but it's a pretty nice place. He even has a jukebox in one corner. That's where he gets his nickname.

He told me that he was so into music as a kid that he used to beg people for money to put in the jukebox at the local bar where his dad worked. I have a feeling his dad didn't actually work at the local bar, but that's just me reading between the lines. Juke left home a couple of years ago and doesn't like talking about his past. Now that I've met Juke in person, I think his nickname also comes from being so naturally wired that he's always shifting on his feet, like he's ready to make a move on you.

The rent is, like, really expensive—$2,000 a month—but according to the people I've met at work, that's a steal for a one-bedroom apartment in Alexandria, even the edgy parts like Barrel Point. I sleep on the couch and have a shelf for my clothes in a crate under the TV. Juke hasn't asked me for money yet—he says he already makes more money than he ever imagined—but now that I have a job, I know I should start chipping in, at least until I find my own place. (That is, if I decide to stay in DC. I've only been here for two months.)

Juke works the nightshift on the network operations team for CyTech. He takes classes during the day at George Mason University. He doesn't have a college degree yet, but he's so good with computers that CyTech hired him anyway, on the condition that he had to keep working toward a degree if he wanted to keep his job.

CyTech is a computer security company that installs and runs private networks for its clients. Juke is a genius when it comes to networking and operating systems. And he knows a ton about data mining; he's kind of like a detective who discovers patterns in large batches of data. Those patterns help people manage their businesses or, in CyTech's case, detect cyberattacks before they happen.

That's how we met. We started exchanging ideas on Hacker News about building a deep-learning app that could learn to play jazz (the other passion we share). Deep learning is a kind of artificial intelligence that gets its name from having many layers of mathematical arrays that act like neurons in a human brain. I don't mean to brag, but I've won several math contests at the state level in Minnesota, and I was the best Python coder in my high school. At first, Juke and I were just fooling around with our ideas and comments, but then we got serious.

Even though Juke is a musician and has more than his share of bass guitars and other audio gear, he doesn't have any brass, so I haven't been able to jam with him.

I miss my saxophone. I call her Locks (short for Goldilocks—corny, I know, but I named her when I was younger, and I'm too superstitious to change her name now). I should have brought Locks with me, but I didn't know what it would be like when I got here, so I left her back in Minnesota. Now that I have a paycheck, I've been looking into picking up a used sax. It would be fun to jam with Juke. Even though we've known each other for a few years and spent countless hours together online, until a couple of months ago, we'd never met in person.

My hands are still shaking by the time I climb the stairs to Juke's apartment, so it takes me several attempts to unlock the double deadbolts he installed on his door. Did I mention that Juke is paranoid? He says it comes with the territory of working in cyber security, but I think he's always been paranoid, and that cyber security was just a good fit for his personality.

Before I even head to the bathroom to check on my injuries, I set my backpack on the kitchen counter to assess the damage. My turkey sub looks like a pita, and I guess the bag of chips burst open when the bottle of Coke exploded. It's all sticky soda and crushed chips inside. Fortunately, my laptop survived the assault. That's because, after my last run-in with the skinheads, I reinforced my laptop compartment with metal plates that Juke stripped out of an old personal computer. Even though the case is tacky to the touch, my laptop boots up fine.

When I'm satisfied, I head to the bathroom. What I see isn't good. Instead of Mohammed Toma, the face of Quasimodo stares back at me. My lower lip is the size of a golf ball, my front tooth is slightly loose (but not chipped, as I initially thought), and my swollen left eyebrow is smeared with blood. If I don't get ice on my injuries, I won't be able to go to work tomorrow. It's not the kind of place that you show up looking like you were in a street fight. Did I mention that I work at the White House? I'm the newest (and youngest) member of the groundskeeper crew.